Developments in Bach interpretation

Introduction

The development of a historically based performance practice began about halfway through the previous century. That is now so long ago that the movement that emerged from it, the so-called Historical Informed Practice, or HIP for short, has its own historiography. In our century, various overviews have appeared in articles and books that map out who the main players were, which subjects were central, what the developments within that movement were. In the period that is the object of the HIP, in particular the 17th and 18th century, music from 30 years ago was already old-fashioned. The HIP has been around for a while now, but is still developing and moving towards later music. Even early 20th century music is played on period instruments, which makes sense when one considers that Stravinsky's Sacre was still played on gut strings.

The organ world has been influenced by this from the beginning. Some pioneers were also organists. But the development has taken on other features here, which has sometimes led to ideas within the rather isolated organ world that seem to contradict the broader HIP, as used by other instrumentalists.

Striking, for example, is the difference in approach that arose between harpsichordists and organists. Although both instruments are operated with a keyboard, the playing methods sometimes seem to be opposite (a modern organist plays everything loose, a harpsichordist everything bound, even over-legato); a situation that in the 17th and 18th century probably never existed, because it always involved the same people who played both the organ and the harpsichord.

The fact that organists have historical instruments at their disposal has strongly determined the insights of organists who were concerned with the HIP. The attention for later organs and the connection in performance practice between instrument and music, also led in the organ world to the realization that, for example, Franck, Reger and Messiaen each deserve their own approach.

The HIP was a response that fit into a broader stream of post-war change. The horrors of the first half of the 20th century made many realize that certain developments that had previously been taken for granted had to be approached critically. Especially in the world of art, old traditions were broken. Modernism broke through. On the other hand, people looked back to times before Romanticism, the period that was accused of cultivating an exaggerated emotional life and breeding false sentiments. The resulting reorientation towards the craft, the rationally structured and more balanced forms of expression also led to an important counter-movement, of which the HIP became one of the manifestations.

A contemporary look back at the HIP

In order to be able to interpret the developments within the organ world, especially with regard to the interpretation of Bach's works, a comparison with the development within the HIP is illuminating. Bruce Haynes, an oboist who experienced the revolution in the approach to early music at close range and has made an impressive career as one of the first baroque oboists, provides an illuminating classification of the movements in the music world in the twentieth century in his book 'The End of Early Music' (Oxford University Press, 2007). It is a very readable book, with listening examples, in which Haynes extensively argues how he arrived at his vision. Contrary to the prevailing view, he not only mentions the Romantic and the Modern way of making music, but he also introduces the Rhetorical way of playing as an alternative for the interpretation of early music.

Reality is always more complicated than the models suggest. Most musicians will have adopted elements from each of these directions in their playing. An organist may have renounced legato in his Bach playing, may not use irresponsible registration changes, and yet cannot resist lingering on a high melodic note, even if it is on a weak section of the bar.

BWV 664, Allein Gott in A, m.50.51: the highest note is halfway through the harmony change,

the accent falls on the dissonance after the bar line

BWV 541, Fugue in G: theme: the upward leaps are melodically interesting, but the harmonic accent falls after the bar line, as is evident in the progression of the piece (schematic bass of the final soprano entry)

Romantic

The Romantic approach emerged from the nineteenth-century way of making music, which continued to have an effect well into the twentieth century. The predominant focus on melody, with the accompanying tension and relaxation expressed by means of rubato and dynamics, is one of the most important characteristics. Expression, often understood as a strong personal statement, with the use of extreme legato, vibrato and portamento, was the goal of making music. This was accompanied by a certain emphasis, which often resulted in slow tempi. Early recordings also reveal a certain sloppiness, which apparently did not bother anyone, but is surprising in our time with digital recordings.

Modern

The Modern approach was in many ways a reaction to the Romantic way of making music.

The subjectivity of the nineteenth century was rejected and dismissed as sentimentality. Rhythmic freedoms were abolished (literally, by a Viennese ‘Stilkommission’ in the 1960s). Equality was pursued down to the smallest note values. The tempo was continuously and strictly maintained (‘click-track baroque’). All notes became equally important, eliminating pulsation. A continuous legato and vibrato only served the long line. The rise of the Urtext editions seemed to serve the attention for the intentions of the composer, but resulted in performances in which the notes were played objectively, which were supposed to speak for themselves in the end. Balance became the norm, which nevertheless sounded like distant uniformity.

Rhetorical

Since in his opinion neither of these directions is suitable for approaching music from before the year 1800 properly, Haynes opposes them to the Rhetorical approach.

Whoever wants to convince his audience must construct his speech well, know all the arguments and counterarguments, he must play on the emotions of the audience, know all possible forms of expression to convey the intended intention. Rhetorical music-making is therefore communicating, calling affects to life, recognizing the right gestures and following the reasoning style that is contained in the music.

The expression of the music is central, not the expression of the performer (Romantic) or the distance of the perfected virtuoso (Modern). Joachim Quantz (1752: 11, par.5) already indicated that the best music can be spoiled by a bad performance, but mediocre music can be improved by a good player.

There has also been a lot of attention in the organ world for the meaning of rhetoric in music. It soon became a buzzword, used at every opportunity to judge interpretations. However, the meaning did not seem to be the same for everyone. The confusion that arose is comparable to that over the term ‘Stylus Phantasticus’, which was thought of as fantastic, especially boundlessly free play. We now know – hopefully – that it means nothing more than ‘style of fantasy’, a genre designation such as the style of the theatre or the church. Rhythmically free play was introduced in the 17th century with the term ‘con discrezione’ (even with the young Bach in Toccata BWV 912 bar 111), which is not so easy to interpret, demands a lot of interpretation from the player. Thus the rhetorical argument in music seemed a carte blanche to perform all kinds of ‘figures’ with great emphasis. Just like old fingerings and articulation curves, this generated attention for the smallest details in the music. The profiling of small units brought more variation to the organ playing, but larger structures were less effective. The goal of the Rhetoric, namely convincing the listener – for which the ‘Figurenlehre’ was only a means – was lost sight of.

Throughout his book, Haynes lists a number of concrete resources that can assist the musician in performing early music:

Agogics: rhythmic freedoms within the beat, ‘stealing time’ (R.North, 1693/1694)

Pulse: An audible difference between heavy and light notes.

Varied articulation, rather than just legato.

Phrasing in ‘figures’, motifs, instead of just long lines.

Let us follow some aspects of these developments as they have emerged within the organ world.

Legato, or not.

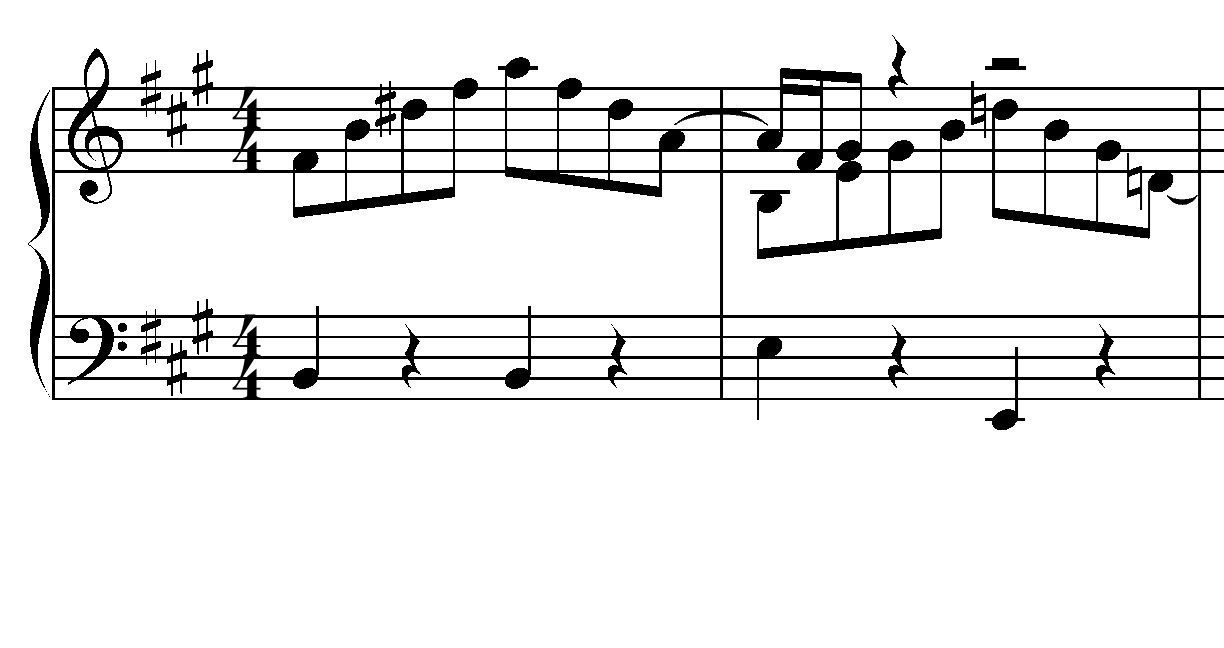

In both the Romantic and the Modern interpretation, legato was (and is) the norm. In the 1960s, organists began to take the sporadic slurs in Bach's keyboard music seriously. The 'group articulation' with small articulation openings according to the note values, brought some nuance. But underneath the slur, modern legato remained. The starting point was an articulation as we find it in the 4nd trio sonata, with slurs per four sixteenth notes. This was considered an 18th century convention and applied to all of Bach's music.

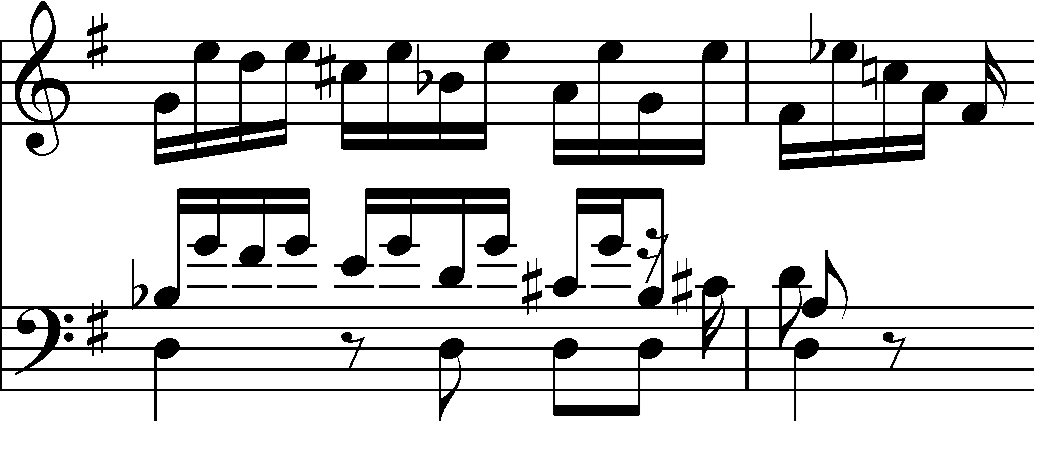

voorbeeld sonate 4, BWV 528

![]()

But after a few decades a new insight emerged: any legato had to be avoided.

Detailed studies (see Lohmann, Artikulation… and many articles in Het Orgel at the same time) showed that before 1800 each note was given its own articulation, in modern terms: non-legato, or better the ‘ordentliche Fortgehen’, as Marpurg called it. A simple principle, which on the organ, certainly in large spaces, led to much more clarity. For those who were used to playing legato this meant a big change. It sometimes resulted in angular organ playing, because the connection between the notes was no longer felt well and each note sounded too emphatically.

In the absence of articulation marks in keyboard music, this way of articulating resulted in an even, yet static sound image.

It is therefore good to present here some data that give a more varied, sometimes even contradictory picture.

The slurs that Bach places in his keyboard music are rarely complete. They seem to want to put the player on a track, but leave the further filling in to the player. It is also striking that these slurs are longer than what is usual for strings and winds.

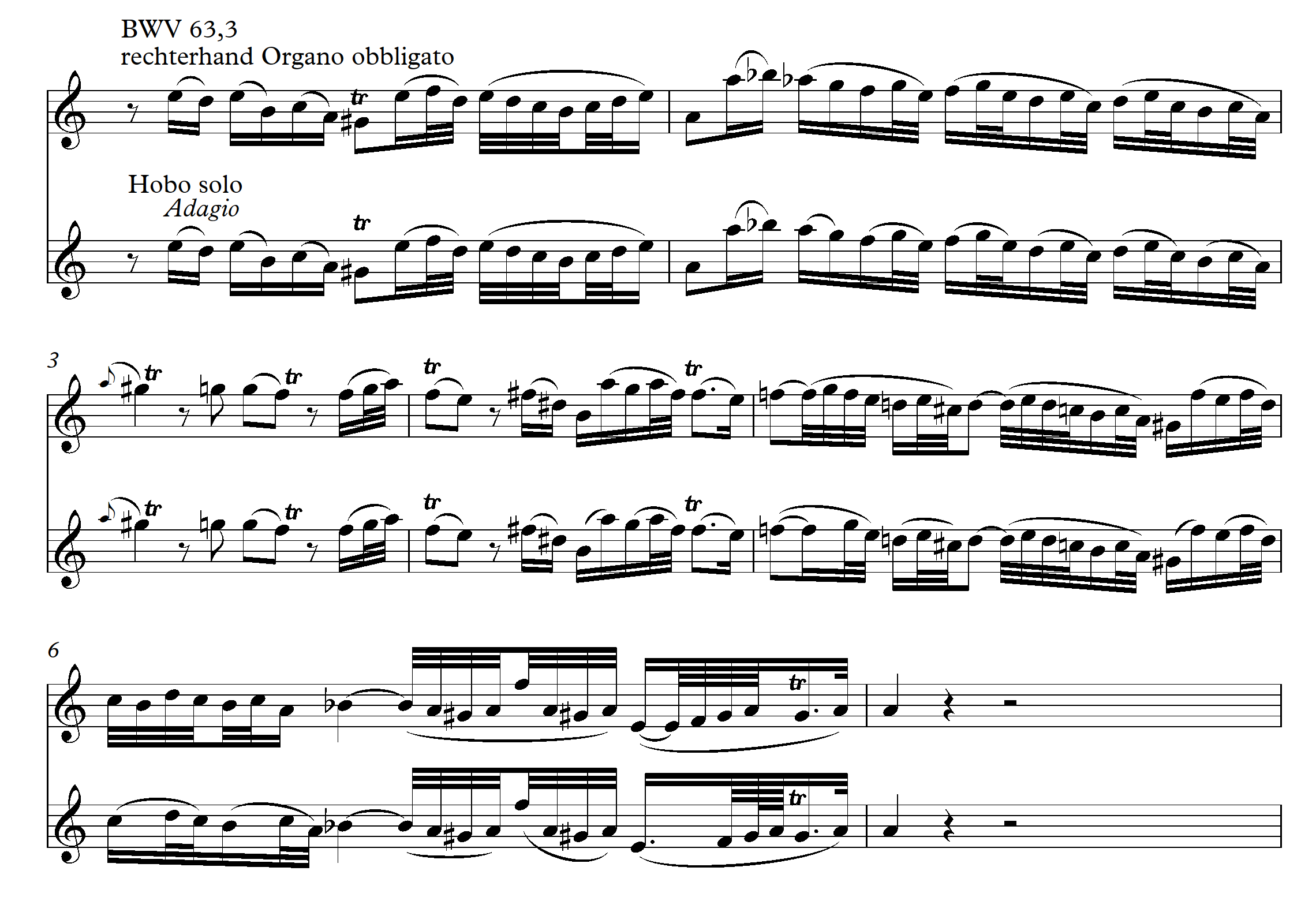

BWV 63, 3, organ obbligato part compared with oboe part in older version.

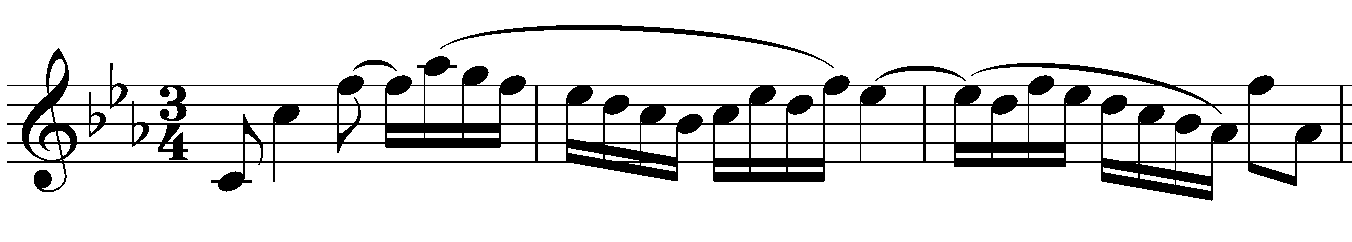

In the slow movements of the organ sonatas there are long slurs (which are not even that easy to compose with a quill), sometimes even crossing a bar line.

BWV 526,2 maat 5-7

Similar slurs are found in the Inventions. (Doesn't the 'cantable Spielart' that Bach mentions in the preface really just mean legato?)

Apparently Bach asks for longer lines here than we would be inclined to play if there had been no bows. Doesn't this also ask for a tempo in which the lines sound fluent, with less emphasis on the smallest motifs? Structures such as the harmonic rhythm, certain 'verse feet' and sequential passages are given a clearer connection precisely by making less important notes inconspicuous. The play of foreground and background, light and shadow (compare baroque painting) determines the progression and course of the music more strongly than just dwelling on details. Incidentally, this also inevitably influences the choice of tempo.

The HIP is strongly influenced by musicology. Many musicians who specialized in early music did research and studied musicology. This resulted in the development of views that led to rather schematic interpretations in the search for old conventions, which were considered ‘lost’ over time. They presented delimited theories that were presented as fixed data and were considered generally applicable. Reports of ‘Organo Pleno’ registrations around the middle of the 18th century were consistently carried through into much older music, old fingerings were even used in Mendelssohn, tempo theories from the late Renaissance led to fixed tempi in Bach, overpunctuation was widely used (which was ridiculed in a more recent study as ‘das Überpunktierungs-Syndrom’), to name but a few examples. It appealed to many: the 17th and 18th century seemed a model of simplicity and clarity, in contrast to the present time. That old time was idealized, the peace, the balance, old music became a kind of refuge, people liked to imagine themselves in ‘wie es damals war’. But isn’t that actually a Romantic trait: in our dreams about then, there, elsewhere it is more beautiful and better? About a time that we can only partly fathom, of which we have too few puzzle pieces to be able to see the whole, in which speculation inevitably plays a role, modesty in our convictions is required. Certainly when opposing interpretations of the same data can lead to – by the way interesting – controversies.

An interesting situation, which in this context sheds a different light on thinking in terms of conventions, occurs in the transmission of Bach's Sonatas for organ and Suites for cello.

There are two important manuscripts of the Organ Sonatas: an autograph and a later copy by Anna Magdalena and Wilhelm Friedemann Bach. The second manuscript contains more articulation marks than the first. Initially, these were not always taken seriously, because they were supposedly invented by mother and son. After research (which made a significant contribution here), however, they appear to have been written by Johann Sebastian himself, who thus ‘improved’ his own version.

There must also have been an autograph of the cello suites that has been lost, but the oldest copy is that of Maria Magdalena. It contains bows that were considered illogical by later cellists. Anna Magdalena is said to have invented them herself – again. For years, these bows were ignored and replaced by ‘improvements’. The Dutch cellist Anner Bijlsma did take the bows seriously (‘Bach, the fencing master’ 2001, also read the article by Frank Wakelkamp, http://www.frankwakelkamp.com/nl/artikel_Bachsuites.html) and concluded that the tradition of bowing according to the conventions of several generations of cellists and musicologists has led to a wrong approach.

If we were to base ourselves solely on the autograph of the organ sonatas and we had not dared to introduce any other articulations, would we not have to conclude, with the ‘knowledge of today’, namely with the second manuscript with original articulations in hand, that we had misunderstood Bach’s intention? At most, we would have applied articulations according to ‘rediscovered’ conventions, which would probably be much more conservative than what Bach gives us in his notes on the second manuscript.

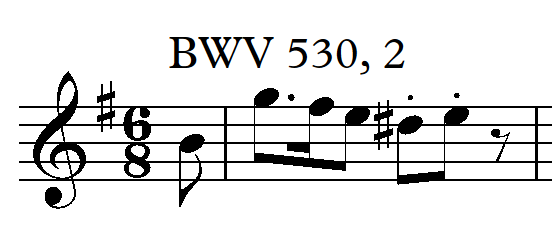

Even illogical and anti-conventional articulations are apparently part of the repertoire of a great composer. What about the dots at the beginning of the second movement of the sixth organ sonata? They are not in the autograph. According to convention, we would probably have played a slur with such motifs.

By taking the lack of notated articulation in old keyboard music literally and only ‘ordentlich’ letting all notes without articulation indication ‘fortgehen’, music sounds too uniform. Without interpreting slurs and dots in the Romantic way by making extreme (pianistic) length differences between notes, a multitude of nuances can be introduced by using all note lengths. The music of a creative genius like Bach demands such a varied soundscape.

“Organists were often frightened when he wanted to play on their organs and pulled out the stops in his own way, believing it could not possibly sound good the way he wanted, but they heard an effect afterwards which astonished them.”

This statement by a contemporary about Bach's registrations which apparently astonished everyone present, can quickly become a license to elevate unusual registrations to the norm. The same could apply to unusual articulations. Only knowledge of the entire repertoire puts the exceptions in the right light and teaches us to use all possibilities in a tasteful way.

Pulse

In baroque music, it is not enough to keep time. A palpable pulse must be created. This is particularly audible in works with basso continuo, where the harpsichord indicates the chord changes. The tempo of the harmony, which falls on the heavy beats, always comes forward more strongly than the light beats. All voices have their own figuration within the bar, but on the heavy beats of the bar they change harmony at the same time, or reinforce it by creating dissonances from ties.

On non-dynamic instruments such as harpsichord and organ, making the pulse audible is not self-evident. From the ‘modern’ approach, the small note values are evenly strung together, as in additive rhythms (where small note values are added together, as is inevitable in, for example, the ‘valeur ajoutée’ rhythm of Messiaen). While in baroque music there is a divisive rhythm: the small note values are no more than a subdivision of a larger beat. Often, the pulse is also felt on too small a note value through slow studying, which became commonplace in the organ world via the Widor-Dupré line, among others. Much of Bach’s music mainly contains eighth and sixteenth notes. This ‘modern’ approach results, especially at slow tempi, in an accentuation of the eighth notes instead of the quarter or even the half.

The difference between heavy and light notes requires a subtle flexibility of rhythm and nuanced timing. In the Romantic approach, this often degenerates into rubato, where there is acceleration towards the bar line. A better way to introduce a difference between heavy and light notes without changing the rhythm is a varied articulation. Within the ‘ordentliche Fortgehen’ notes can be played longer or shorter, and in the case of chord breaks perhaps even deliberato. Sometimes a composer gives the player a hint on how to differentiate between note lengths, but here lies a task for the performer, even if the notation is uniform. Just as a speaker cannot recite his text monotonously, music cannot do without an interpreter who shapes the character of the movement and applies well-measured accents at the right moments.

Prelude in G BWV 541 bars 68-69: before and after the barline there is a difference in note lengths, adding nuanced 'dynamics':

The pair of concepts Qualitas intrinsica and Qualitas extrinsica (proposed by Bach’s nephew J.G. Walther, among others), the inner and outer value of the note (named in Engramelle as ‘durée’ and ‘silence’, see Dom Bedos), offers a historical framework for a varied and free handling of note lengths. Depending on the place in the bar, the character of the movement and the affect, no note needs to be played in its full length. The differentiation of note lengths can in this way be just as suggestive as light and shadow in the visual arts of the Baroque.

Also in the early 19th century was still aware of the significance of pulse in music.

For example, we read in the Theoretisch-praktische Orgelschule by Ludwig Ernst Gebhardi (ca. 1837):

‘The good beat must… also be emphasized on the organ, just as on other instruments, so that it can be clearly distinguished from the bad one: for only when the these heavier or lighter accents recur in regular moments does a piece of music receive beat or meter.’

Within the HIP occured also countermovements. The agogical accentuating was resented after a period of exaggeration. A strict rythm came into fashion. The interpretation existed from then on in the art of diminution and ornamentation. The calm and peace that was looked for in old music, as a contrast with the restless modern time, was replaced by a compelling, fast manner of playing. Actually hunting the favorite activity of the art-loving nobility, in the theater one experienced extreme expression of emotions, one sought a vibrant lifestyle.

Without doing injustice to either approach, we can recognize reactions to previous movements in both directions. A recognizable course of events, which in the 17th and 18th century will not have been different. But there is certainly no uniform approach to old music after more than half a century within the HIP.

Tempo

An important theme among organists when interpreting early music is tempo.

Especially because quite strong opinions emerged, in which tempo was regarded as a fixed fact, as concretely traceable as the correct notes from an autograph, opposing views arose. Data such as the 2:1 tempo ratios in Quantz were simply applied to all music. Talsma's halved tempo theory (Wiedergeburt de Klassieker) was embraced with approval by many organists. Theories about fixed tempo relationships were strictly applied. Old tempo tables were translated into metronomic rules. This usually resulted in slower tempi than usual in the HIP.

Historical data were combined and presented as rediscovered conventions that could provide the performer with a pleasant framework.

This of course provided an interesting field for discussion and gave rise to sometimes diametrically opposed opinions, in which it was argued that all old music should be played as quickly as possible.

It is a given for organists that organs in churches with a lot of reverberation sound unclear. In order to be able to follow the music well, the tempo should not be taken too fast. When it was accepted a few decades ago that the great Bach works should all be played ‘in Organo Pleno’, the acoustic problem was further aggravated.

In the large Gothic churches in the Netherlands, where the organs often well into the 19th century were tuned to mean-tone and almost exclusively the Psalms of David were tolerated, a homophonic plenum sound must have sounded beautiful. But on our famous baroque organs in the 18th century probably never played Bach. Now that almost all baroque organs have been tuned in a more modern temperament, it is inevitable that we will also want to play music by Bach on them.

But the acoustic conditions are completely different from those in the churches of Thuringia and Saxony in Bach's time, where built-in pews and other furniture strongly absorbed the reverberation. Instead of traditional 16th and 17th century large front pipes, which often speak slowly, the fast-speaking Quintadeen 16' was popular throughout Germany as the basis of the large plenum. The Dutch situation cannot be compared with that of Bach's environment. Uncritical Bach playing on the full organ is more reminiscent of 19th century monumentality. The beauty of old instruments as we hear them in baroque ensembles, whose qualities lie in both alignment and fusion, is far removed from this.

A study has also recently been published on the subject of tempo, describing the development of both old and modern theories of tempo. In ‘On Bach’s Rhythm and Tempo’ (Bärenreiter, 2011), Ido Abravaya shows a picture of changing tempo usages rather than fixed conventions, and he uses good examples to capture inconsistent situations in a broader vision.

It is interesting how he demonstrates different ideas about tempo already in the Baroque period (p.53 ff.). Quantz (1752) writes about ‘in previous times’, when everything was played almost twice as slow. While Mattheson in Das neu-eröffnete Orchestre’ (1713) states the opposite: ‘how strongly in recent years the quick and great ability especially on instruments was admired’. We do not know exactly to which music these remarks refer, but it does indicate that we cannot draw generally valid conclusions on the basis of isolated quotations.

Apparently, tempo choice was already subject to change at that time. In the Obituary that appeared shortly after Bach's death we read: “In conducting he was very accurate, and in tempo, which he generally took very lively, abolutely certain" (probably a contribution by C.P.EBach). This indicates that there were already different opinions about tempo at that time and that Bach took the tempo faster than was considered usual at the time. Perhaps Bach also developed in his handling of tempo during his long musical career and for that reason alone there is no fixed tempo to determine for the performance of his music.

In our day, with recordings available all over the world, through which musicians mutually influence one another, there is perhaps more unity of opinion (occasionally contested and broken) than in an age when travel was impractical, some towns and courts were relatively isolated, fashions could vary from region to region, and the pace of development was not driven by fibre-optic cables.

Abravaya makes clear how in the 20th century fixed tempo values were ‘discovered’, which do not hold up well under closer examination. The same applies to the fixed tempi of time signatures or tempo words.

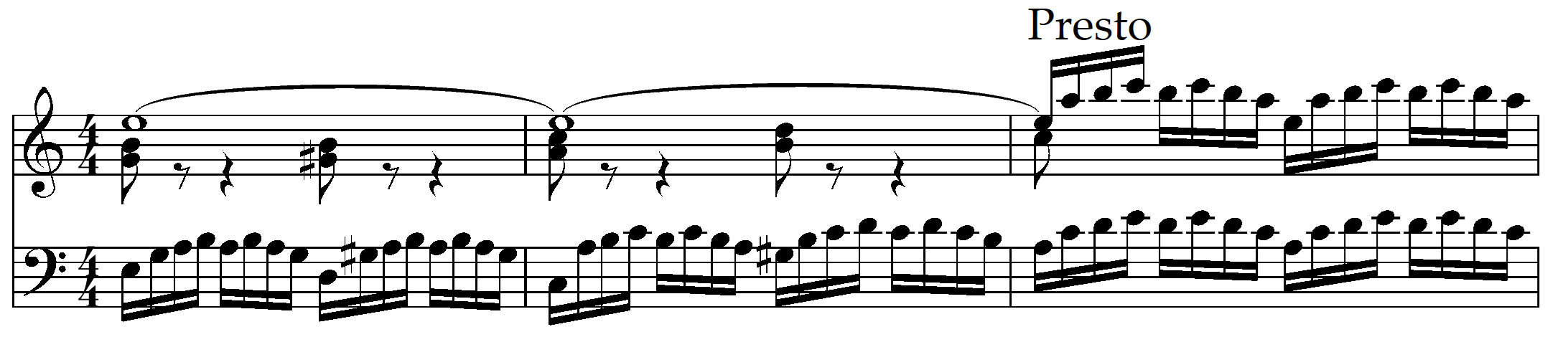

Preludium in e, BWV 855

In this Prelude from the first part of the Wohltemperierte Clavier, there is unexpectedly the word ‘Presto’ without any further indication or change in time signature. Apparently it was possible to change tempo within a movement. And perhaps the two bars before can even be interpreted as an acceleration towards the new tempo?

O Gott, du Frommer Gott BWV 767

A similar situation occurs in the last variation of the partita ‘O Gott, du frommer Gott’, where the tempo word Andante indicates a change of tempo, and as a consequence perhaps a slowing down in the bar before.

In these cases one could apply a 1:2 ratio, as Quantz indicates between his different tempo categories. Musically this is not really satisfactory. Quantz's theory is also not consistently applicable according to later comments.

Also fixed tempo ratios between successive parts, as in the 16th century, cannot always be strictly adhered to. In large series of variations such as Frescobaldi's Cento Partite and Bach's Goldberg Variations, the time signatures cannot be linked to an absolute tempo value, although modern commentators like to speculate on this.

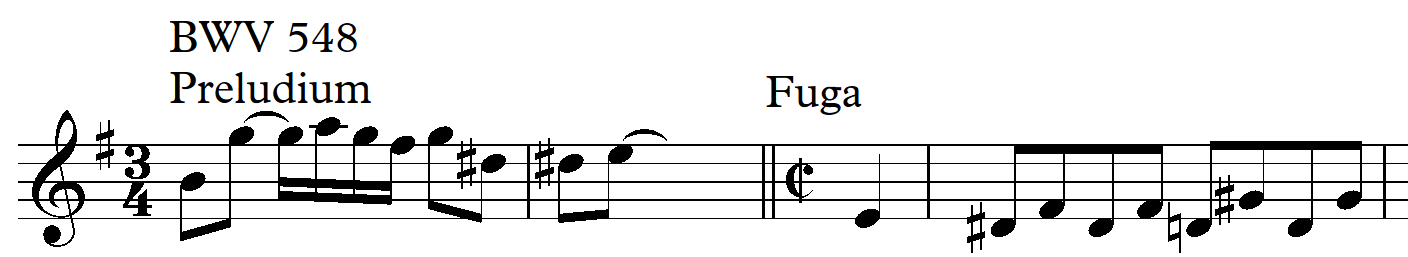

Consecutive movements such as Prelude and Fugue often seem to be connected in simple proportions such as 1:1, 1:2 or 2:3, the proportio sesquialtera. In these cases, it is musically important that the pulse continues, but that the subdivision varies.

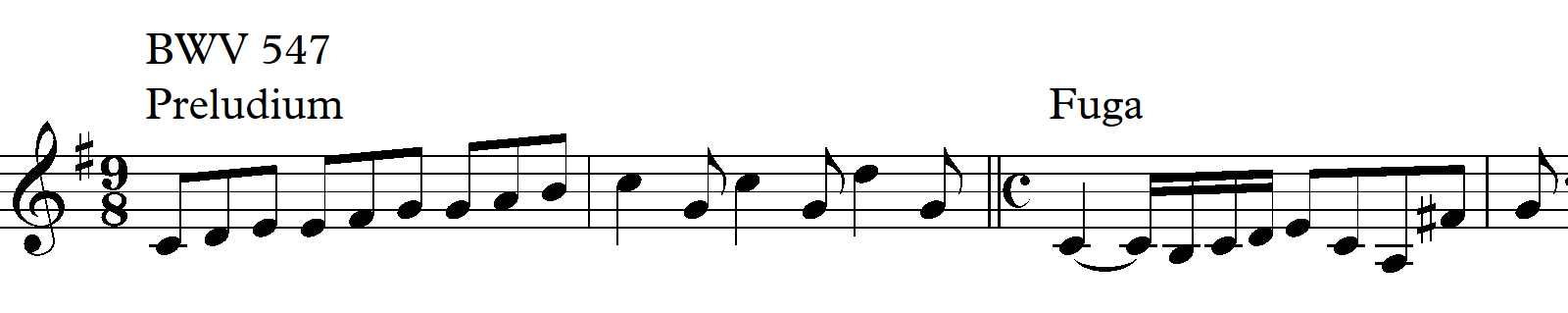

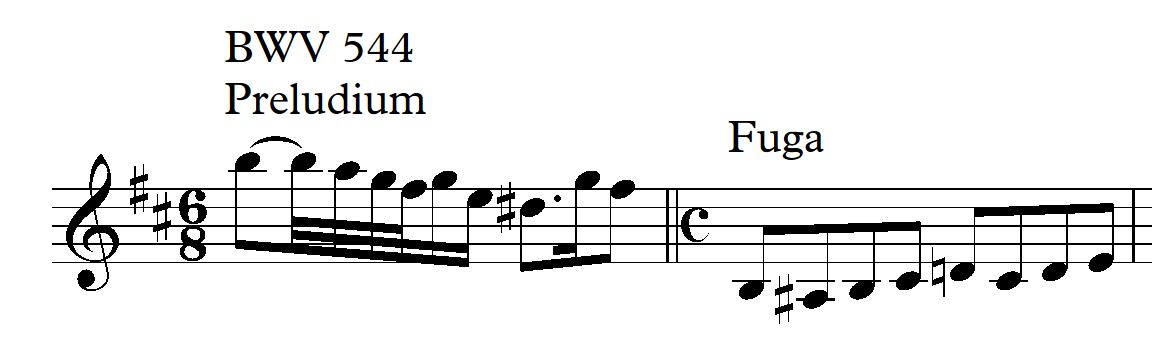

In the Prelude and Fugue in C major, the ratio 9/8 to C can be easily translated (3/8 becomes ¼).

Also in the Prelude and Fugue in B minor, the 6/8 time can be translated to the C of the fugue (half a bar is half a bar; the Prelude should then not be played in eighth notes, but with a pulse per half bar).

But it becomes difficult when a ¾ bar changes to an allabreve bar, as in the Prelude and Fugue in E minor. Without a metronome, it is not possible to simplify this to a fixed tempo ratio, even if that would lead to a satisfactory result. (Or the Prelude becomes too fast, or the Fugue too slow; perhaps the allabreve notation here mainly suggests a broadening compared to the Prelude?).

Conclusion

A great composer like Bach could not be forced to remain within fixed frameworks, not even retroactively from 20th century views. Discovering the creativity and artistry in his music lies not so much in noting similarities as in seeing the richness of differences. The two parts of the Wohltemperierte Clavier, with only Preludes and Fugues, are already incredible in their diversity. Even in often predictable works such as Fugues, Bach seems to be able to renew the form again and again. With each new work by Bach that we get to know, we recognize similarities and learn to understand the style better, but it is precisely the uniqueness of each work that determines our fascination for this music.

All the different views on Bach certainly stem from that same fascination, and will continue to occupy us in the future.