Buxtehude's Ciaconna in e minor is too short

Numbers of variations in works with ostinato basses in the 17th and 18th centuries in Germany.

Introduction

Buxtehude's Ciaconna in E is too short

Buxtehude's Ciaconna in E is too short.

Numbers of variations in works with ostinato basses in the 17th and 18th centuries in Germany.

But the early history of this form shows irregularity: changing basses, variations in time signature and key within one and the same work. A beautiful example of this is the monumental ‘Cento Partite sopra Passacagli’ by Frescobaldi, in which the composer also names the different variations: Passacagli, Ciaconna, Passacaglia Altro Tono, even a Corrente passes by.

A regular arrangement of the number of variations, without changes in bass theme, time signature and key signature occurs from the second half of the 17th century in Germany, such as with Pachelbel, whose Ciaconnas are set up in groups of ten. 1On the other hand, some composers appear to compose both regularly and fairly randomly constructed works in this genre. With Fischer we find both tendencies. With Böhm we find a very irregular picture in the Chaconne in D, with different basses and even some freely modulating passages. The title Ciaconna (or Chaconne) or Passacaglia seems to indicate in Germany also in this period a work with a varied structure, although more strictly organised versions were also made.

Buxtehude

Buxtehude occupies an interesting position in this context. In addition to the three works for organ, we also regularly find ostinato basses in his cantatas and sonatas. In general, however, the number of variations varies greatly. Regularity is not the norm, there is even a theme of three and a half bars. Buxtehude dealt creatively with this form.

Among Buxtehude's organ works, the Passacaglia in D minor stands out for both the regularity and the variation in the structure. Instead of ten or six variations (as is customary in the French tradition), Buxtehude opts for groups of 7 variations.2 He made an original choice in varying the key of the four groups of seven variations: in tonic, parallel, dominant and finally of course tonic again, connected by three short, freely composed modulating transitions. All the changing elements that his colleagues used are present, but the order is balanced and regular.

When analyzing the Ciaconna in C minor, we discover less structure, except for the striking caesura right in the middle of the piece: in bar 77 a passage of five bars begins in which the theme is absent.3The work then continues in the same way, without a clear structure in the number of variations, which are sometimes repeated and sometimes not. become. The ‘free’ bars seem arbitrary, could even have been added afterwards (to freshen up this long work a bit?).

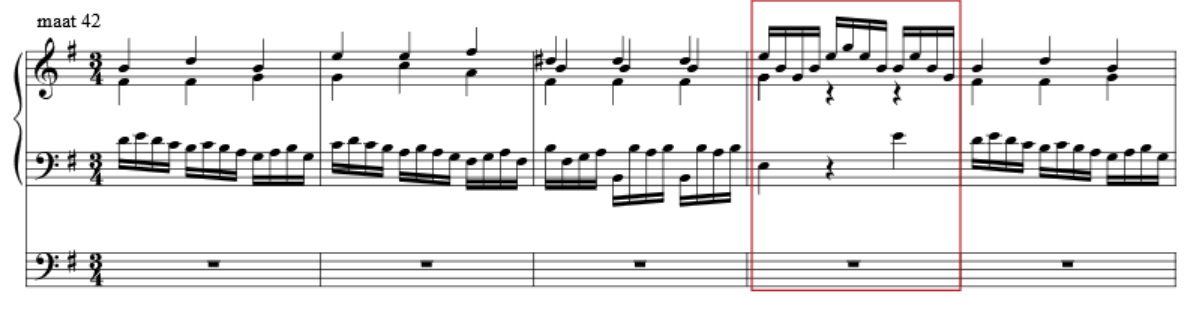

In the Ciaconna in E minor the structure is clear: always groups of 2 variations, where the second (sometimes with a small variation) repeats the first. But in all existing versions one variation is missing, namely the repetition of the eleventh variation. Given the otherwise very regular structure, it is clear that this variation does indeed need to be repeated. In the Andreas Bachbuch, the most important source for the work, it can be seen that at the beginning of this variation there is a kind of repeat sign (the only time in this work, and somewhat unclear at this point). Apparently it was forgotten to notate it again after four bars.

A small transition is needed; the example gives a suggestion for bar 45, after which this variations is repeated from bar 42.

If the variations are now counted in pairs, 16 groups are created. Two groups of six and a final group of four can be distinguished.

The second group of 6 has a striking beginning, with a calmer rhythm, after the rhythmic build-up in the first part. The conclusion of this group has a similar calm rhythm, now intensified by chromaticism and even a different bass. In the last group of 4, the repetition of the variations is broken, which gives the work a liveliness through the succession of ever new variations, which also contrasts with the conclusion of the second group through a constant sixteenth-note movement. Only at the end is the repetition applied again.

Buxtehude does not necessarily adhere to the predetermined choice of groups of six repeated variations here. At the end of the second group, he dares to become freer and starts the last group with new élan, which incidentally connects to the beginning again through the repetition at the end.

But, although this may hardly matter to the audience, we do the work more justice by playing the missing repetition.

Bach

The connection between this tradition and the ultimate Passacaglia for organ, that of Bach, calls for a comparison. Did Bach write his work with a predetermined structure, did he apply elements from the existing tradition, or is his ingenuity as a composer paramount in this work?

After the first solo pedal entry, the work has 20 variations, neatly in line with tradition. Peter Williams (The Organ Music of J.S. Bach) provides an overview of a number of analyses by various authors, which only agree on a few points. Or should the pedal entry be included, so that there are 21 theme entries?

It is then tempting to make the Golden Ratio division4 hich seems to fit well: a group of 13 entries and a group of 8 entries (again to be divided into 3 manualiter variations and 5 variations with pedal); although of course this is also speculative.

The solo pedal entry seems exceptional in the light of tradition. Yet we find basso ostinato compositions in which the theme precedes the variations. It is not unusual in Purcell and Schmelzer. But Bach certainly knew the works of Buxtehude well. In his Sonata in B flat for violin, gamba and basso continuo, in the original version the theme is notated only in the bass for the first time.5 In the last part of the Praeludium in g (BuxWV 148), also a Ciaccona, Buxtehude also has the pedal enter alone.

From the tradition that Bach came to know, more comparisons can be made with his own Passacaglia. After the pedal entry, Bach seems to start with repeated variations, but soon abandons this, although he returns to it at the end – thereby creating symmetry. The elaboration of the figures that Walther mentions in his Praecepta Musica (figura corta and suspirans), as we know them from many of the chorales in the Orgelbüchlein, seems to have been his next – fairly traditional – goal. This creates irregular groups of variations (two times figura corta and four times suspirans). The tenth variation that follows offers a completely different, more modern course: a solo that starts on the highest note, combined with a continuo setting of pedal and left hand. The solo continues in variation 11, the beginning of the second group of ten variations, which is also clearly marked by the fact that the theme is no longer in the bass but in the soprano. All in all an ambivalent situation: does something new begin in variation 10, or in 11, or is this a way to introduce layered structures, to experience the progression in different ways, thus avoiding a strict, vertical division of the variations? Incidentally, this approach quickly leads to a conclusion, after which three manualiter variations follow in which the theme is introduced rather concealedly. The last five variations, with the theme in the pedal again, offer a greater variety of textures than the beginning, changing per variation and thus an intensification, with the exception of the last two which, as indicated, again show repetition.

Did Bach, in this rather early work, perhaps work more or less associatively, using all sorts of familiar techniques and kneading them into a composition that is more monumental and effective than any of his predecessors?

Comparing it to works he probably knew provides enough to suspect that Bach could already draw much inspiration from them for his fantastic creation. All speculative classifications of variations into groups offer less support and may also have sprung from a 20th century music-theoretical approach.

1 The Ciaconnas in F minor and F major each have 40 variations, the one in D minor 30; the repeat signs apparently do not count for the composer.

2 This anomalous number, which we also find in the two times seven Sonatas opus 1 and 2, and the seven Suites for harpsichord on planetary names, which have not been preserved, has been pointed out by several authors. It is associated with the precious astronomical clock that was present in the Marienkirche in Lübeck.

3 Earlier, from bar 29, a similar passage could be heard after a rather random fugato, which should actually have been followed by the eighth variation.

4 The numerical sequence created by adding the previous two numbers: 1,2,3,5,8,13,21,etc.

5 In the edition Buxtehude adds a few notes for the violin, which anticipate the first variation; see K.Snyder, 2007, p.349).